Electronic products run pervasively through our modern lives, found almost everywhere. They are an integral part of our daily life and at the heart of many products that have risen from their “nice to have” status to “indispensable”.

There is however a harsh reality that accompanies the use of electronics; as these systems and devices become more powerful and compact, they generate growing amounts of heat, which is known to severely impact performance and longevity. Thermal management in electronics has thus become a critical concern for engineers and manufacturers.

Thermal management

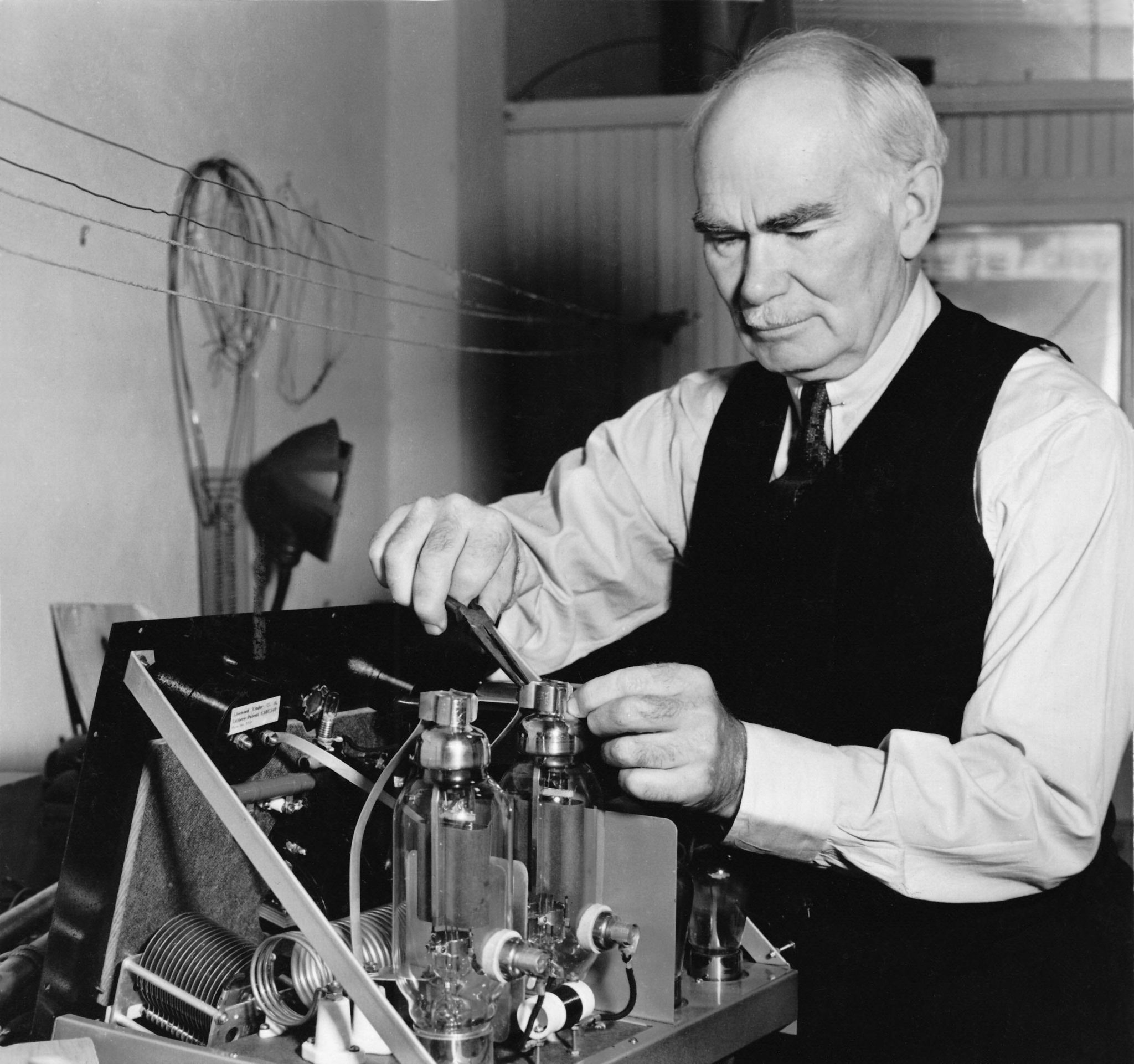

Heat generated by electronics has been known since the days of the glowing vacuum tubes invented by Lee Deforrest and originally used in the first radios (Figure 1) and later in televisions. They were also used in the first massive computers like ENIAC, which used some 18,000 of these tubes, requiring cooling of the room the ENIAC was located in. One apocryphal goes that there were technicians on roller skates moving around the room changing the tubes as these frequently burned out.

Figure 1: Lee Deforest’s wireless audio signal amplifier – i.e., the first radio

The transistor significantly reduced the power requirements but with its shrinkage doubling every 18-24 months, in accordance with Gordon Moore’s predictions in his landmark paper “Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits” published in Electronics magazine in 1965, the challenge of thermal management has not abated but become even more challenging, making thermal management increasingly important.

Fundamentally, thermal management is the process of controlling the temperature of electronic components to ensure they remain reliable and efficient. Hence, effective thermal management is essential for the continued development of smaller, more powerful and more energy-efficient electronics, as well as those required for high-energy and high-power applications. In response, engineers continue to develop innovative solutions such as advanced cooling systems and materials with superior thermal conductivity.

Another power-hungry, hence large heat-dissipating sector, is that of high-performance computing required by data analytics, scientific research and artificial intelligence. Liquid cooling and phase-change materials are regularly found in data centres, and supercomputers are located near bodies of water and flowing rivers for their cooling needs.

In the automotive industry, too, especially electric vehicles (EVs), powerful battery systems and electric motors generate substantial heat during operation. Videos have surfaced where EVs burst in flames due to runaway heat. All these systems require effective thermal management to ensure their safe performance, and liquid cooling for batteries are also emerging as a trend in EV design.

Renewable energy products, such as solar panels, wind turbines and the like, use sophisticated power electronics for energy conversion and grid integration. Such power components must commonly operate under challenging conditions and thus heat generation must be managed to ensure both their reliability and efficiency.

Getting the heat out

In principle there are three methods for heat transfer in order of efficiency – conduction, convection and radiation; combinations of these are also common. Still, as one long time axiomatic saying among thermal engineers holds, when it comes to managing the heat: “It all goes back to air”. In the long view, this remains true but the paths to getting “back to air” can be complicated.

Air cooling is thus, and not surprisingly, the most common method of thermal management for electronics. It can be active (fans), passive (heat sinks) or a combination (including heat pipes) to dissipate heat into the surrounding air. Engineered advances in fan design, including blade geometry and speed control, continue to improve the efficiency of air-cooled systems.

Liquid cooling systems use a coolant (usually water or a specialised liquid) to transfer heat away from electronic components, much like the radiator of internal combustion engine cars. These systems are more efficient than air cooling alone and are often employed in high-performance computing environments. Liquid cooling can either be single-phase or two-phase, with the latter offering even greater cooling capacity.

Figure 2: Experimental setup for direct liquid cooling of an IC (courtesy Georgia Technical University)

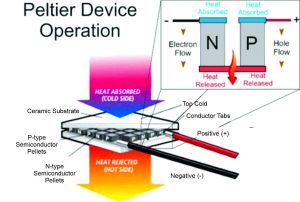

Solid-state cooling is another option, known as thermoelectric coolers (TECs). These use the Peltier effect to create a temperature difference under electric current. They are unique in that they can both cool and heat electronic components, somewhat like the heat pumps used to heat and cool homes. This dual capability makes them a versatile solution for precise thermal management; see Figure 3.

Figure 3: Peltier device operation illustration

Phase-change materials (PCMs) are another option. These are substances that absorb and release heat during phase transition, say from solid to liquid, etc. In electronic devices PCMs act as thermal buffers, effectively absorbing excess heat and releasing it when the temperature decreases. They have proven most useful in applications where rapid temperature changes occur such as in hot spots on IC chips; see Figure 4.

Figure 4: The operating principle of a phase-change material

There are other solutions available, including newer materials with engineered properties that far exceed those of natural materials. Thermal interface materials (TIMs) deal very successfully with chips’ hot spots. TIM examples include graphene-based materials, which are an-atom-thick sheet of carbon. Their thermal conductivity properties are exceptional, so researchers have been exploring them as heat spreaders and for various other applications.

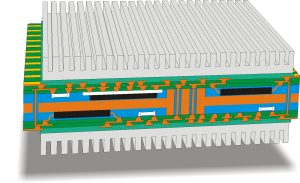

Finally, there is integrated thermal management, wherein the entirety of the electronic module or assembly is created with a thermal solution integrated into it. This is increasingly seen in heterogeneous integrated packaging solutions. This has also been the objective of the Occam Process first described by Verdant Electronics. In such structures, the electronic assembly is built on the heat spreader in a reverse manufacturing process. This is done without using solder, thus bypassing a stressful thermal excursion in the manufacturing process; see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Cross-section of a prospective integral thermal management solution described by Verdant Electronics, with both internal and external heat sinks offering 3D thermal relief

Engineering a solution

It’s worth noting that while in the past much effort was of the trial-and-error type in dealing with thermal management challenges, with computers getting better all the time, computational techniques and finite element modelling software for thermal investigations have become indispensable tools. Today, engineers can design assemblies and simulate their thermal behaviour, to optimise their cooling solutions before ever making a product prototype.

By Joseph Fjelstad, CTO The Occam Group